The Central Axis of Beijing: The Heart of China’s Ancient Capital

Beijing, the capital of China, is one of the globe’s most historic and culturally rich cities. One of its most wonderful things is the Central Axis of Beijing. This axis isn’t a road, nor a straight line — it is a symbolic backbone of the city that has a voice for more than 700 years of Chinese urban planning, culture, and imperial power. Beijing’s Central Axis runs 7.8 kilometers from the Bell and Drum Towers in the north to the Yongding Gate in the south. A number of Beijing’s most famous landmarks follow this axis, including the Forbidden City, Tiananmen Square, and the Temple of Heaven. Let us stroll on this marvelous axis, study its historical importance, admire its architectural magnificence, and discover the regions around it that make it a world treasure.

The History of the Central Axis

The Central Axis first formed during the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368), when Dadu was still the name of the city. Subsequently, it was continued by the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1912) dynasties. The planners designed the city in line with Chinese cosmology, which was sensitive to balance, order, and harmony. The axis represented the authority of the emperor and heaven and earth union. The emperor as the “Son of Heaven” occupied the center and his palace — the Forbidden City — the center of this line. All the buildings along the axis were designed carefully. Temples, gates, towers, and squares all followed this symmetrical form, revealing the importance of order in Chinese society.

The Layout of the Axis

The Central Axis starts from the north and leads up to the south, following the traditional Chinese belief that north is the direction of protection, and south is the direction of prosperity. North-south, the major attractions along the Central Axis are:

Bell and Drum Towers

The Bell and Drum Towers sit at the northernmost end of the Central Axis. The ancient towers were built during the Yuan Dynasty and later reconstructed under the Ming Dynasty. The Drum Tower housed large drums that were used to indicate time in the old city. The Bell Tower held a massive bronze bell that rang in the early morning. They helped citizens tell time together before the invention of clocks. Today, visitors can scale these towers and get a bird’s eye view of Beijing’s old hutong neighborhoods. The thumping of the drum show, still done daily, brings back the nostalgic feel of old-time Beijing living.

Jingshan Park

Only south of Drum and Bell Towers lies Jingshan Park. The imperial garden in the back of the Forbidden City, it once was. The park is perched at the top of an artificial hill, built out of the earth dug up to form the moat of the Forbidden City. Atop Jingshan Hill is a pavilion with one of the best views of the Forbidden City. From there, tourists have in front of them the entire golden-roofed palace complex centrally positioned along the Central Axis. Jingshan Park is even a popular morning exercise, tai chi, and social hotspot among locals.

The Forbidden City

The Forbidden City, also called the Palace Museum, is located at the center of the Central Axis. It accommodated 24 Ming and Qing emperors. It was built from 1406 to 1420 on 720,000 square meters of land and has 9,000 rooms. The city was “forbidden” because only the emperor, his family members, and invited guests had permission to enter. It embodied the emperor’s supreme power and god-like nature. The Forbidden City boasts strict symmetry in design along the Central Axis. The central line on which the main halls — Hall of Supreme Harmony, Hall of Central Harmony, and Hall of Preserving Harmony — lie. Red walls, golden roofs, and grand courtyards demonstrate the grandeur of imperial China. It is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the world’s most-visited museums.

Tiananmen Square

Traveling south, we come to Tiananmen Square, one of the world’s finest public spaces. It lies directly in front of the Tiananmen Gate, which is the entrance to the Forbidden City. It covers an area of 440,000 square meters and has the capacity to hold over a million people. It is surrounded by major national buildings like the Great Hall of the People, National Museum of China, and the Mausoleum of Mao Zedong. Thousands of tourists visit daily to witness the flag-raising ceremony at sunrise and the flag-lowering ceremony at sunset. The soldiers carry out the ceremony with the highest level of precision, symbolizing national pride and unity. Tiananmen Square is not only a historical monument but also a symbol of modern China’s spirit.

Qianmen Gate

Next on the axis is Qianmen Gate, also called the Front Gate. It was initially a part of Beijing’s ancient wall as well as the south gate of the imperial city. It has a tall watchtower and an archery tower. In between lies a courtyard where soldiers used to train and guard the city. These days, Qianmen is one of the busiest areas in Beijing. Ancient buildings renovated in Old Qianmen Street offer shops, cafés, and street performances, an active combination of new and old Beijing.

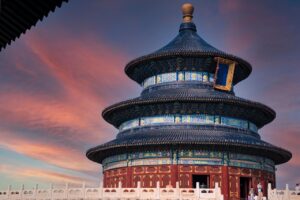

The Temple of Heaven

More to the south, the axis runs through the Temple of Heaven, another masterpiece of Chinese architecture. The temple was built in 1420 and was where emperors prayed for abundant harvests and made sacrifices to Heaven. The main building, the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests, is positioned exactly on the Central Axis. Its dome represents heaven, while the square base represents earth — reflecting harmony between the two. Surrounded by a peaceful park with ancient cypress trees, The Temple of Heaven is walked through many mornings by locals for tai chi, music, and strolling. The mood surrounding it is peaceful and spiritual.

Yongding Gate

At the southern point of the Central Axis is Yongding Gate, also known as “Gate of Eternal Stability.” It was originally built in 1553 under the Ming Dynasty as the primary entrance to the outer city. Although it was ruined in the 1950s, it was reconstructed in 2005 to restore the original alignment of the city. Today, it marks the end of the ancient axis and the beginning of the modern cityscape. The gate symbolizes the continuity of Beijing civilization, linking historic past and modern present.

The Modern Extension of the Axis

Characteristically, the idea of the Central Axis is extended even beyond its original line. Today, in modern urban design, Beijing has carried the idea southward to include modern icons like the Beijing Olympic Park, Bird’s Nest Stadium, and National Aquatics Center. This shows that Beijing’s tradition and modernity walk side by side, keeping the heart and soul of the city and embracing the future.

Cultural Meaning of the Central Axis

The Central Axis is more than a sequence of buildings. It represents the ancient Chinese concepts of harmony, man and nature, and heaven and earth balance. It proves that urban planning can be filled with deep significance. The axis integrates political power, religious belief, and social life. China asked UNESCO in 2022 to inscribe the Central Axis of Beijing into the World Heritage list as a living image of China’s culture.

Things to Do Along the Central Axis

Visitors in Beijing can experience many exciting activities along the Central Axis.

They include:

- Walk or ride a bike all the way along the axis to feel the city’s rhythm. Walk through the Forbidden City and admire its majestic halls.

- Observe the flag-raising ceremony in Tiananmen Square. Ascend to the Drum Tower to view old Beijing.

- Walk along Qianmen Street and savor traditional snacks. Sit back at Jingshan Park during sunset. Visit the Temple of Heaven during early morning exercise by locals.

- Snap photos of the Yongding Gate with the cityscape at the background. Every stop reveals a piece of Beijing’s long and picturesque history.

Festivals and Events

Beijing’s Central Axis also serves as a center for cultural celebrations and national holidays. The axis is illuminated by lanterns and firecrackers during Chinese New Year.

The National Day parade passes through Tiananmen Square, where China shows off its pride. Tourists during the months can experience the color, music, and harmony of the Chinese people.

Conclusion

The Central Axis of Beijing is not just a line of old monuments. It is Beijing’s central hub, China’s cultural thinking, and a living evidence of its civilization. From the Bell Tower at the northern end to the Yongding Gate at the southern tip, the axis is a story of emperors, harmony, and time. Its outer districts — the hutongs, lakes, parks, and squares — show how life in Beijing still thrives alongside this sacred line. The Central Axis is walking through history. Every step, every building, and every stone speaks the story of a city that has stood for over seven centuries. Beijing’s Central Axis is not just a part of the city — it’s the city’s heart, linking its ancient grandeur to its new destiny.